USE OF HBA1C IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF METABOLIC SYNDROME

Trong Nghia Nguyen1, Hoang Thi Lan Huong1, Anh Khoa Phan2, Trung Hieu Pham3,

Thanh Dat Nguyen1, Van Loc Nguyen1, Tran Thua Nguyen4*

1Endocrinology – Neurology – Respiratory department, Hue Central Hospital

2Emergency and Interventional Cardiology department, Hue Central Hospital

3Nephrology and Musculoskeletal department, Hue Central Hospital

4General Internal medicine and Geriatric department, Hue Central Hospital

DOI: 10.47122/vjde.2022.53.7

ABSTRACT

Background: Metabolic syndrome refers to a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors, including abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia. An effective detection of a metabolic syndrome reflects the prediction risk of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. It helps to plan for a management strategy that could reduce the healthcare burden on society. Recent studies aimed to compare the use of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) to fasting plasma glucose as the hyperglycemic component in metabolic syndrome diagnosis. This study aims to compare HbA1c to fasting plasma glucose as the hyperglycemic component in metabolic syndrome diagnosis in the study subjects and determine the cut-off value of HbA1c for predicting metabolic syndrome in the study subjects. Method: A cross-sectional study of 338 non-diabetic adult subjects for health examinations at Hue Central Hospital. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the IDF, NHLBI, AHA, WHF, IAS, and IASO (2009). Waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and biochemical (triglycerides, HDL-C, fasting blood glucose, and HbA1c) were determined. Receiver operating characteristic curves were generated to assess sensitivity and specificity for different cut-off values of HbA1c for predicting metabolic syndrome. Results: The prevalence of metabolic syndrome (model 3: glucose hoặc HbA1c) was 43.8% (148 subjects) higher than the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (model 1: glucose) was 36.7% (124 subjects) (p < 0.05). The optimal cut off point for HbA1c for predictor of metabolic syndrome as 5.5 (AUC: 0.756, sensitivity: 72.3%, specificity: 71.6%). Conclusion: This study suggests that the potential role of HbA1c might be used as a diagnostic criterion for metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, HbA1c.

Main correspondence: Tran Thua Nguyen

Submission date: 19th Oct 2022

Revised date: 19th Nov 2022

Acceptance date: 19th Dec 2022

Email: tranthuanguyen23@gmail.com

Tel: + 84 234 903597695

1. BACKGROUND

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) refers to a group of cardiovascular risk factors that include abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, elevated

blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The effective detection of MetS not only helps to predict the risk of diabetes (DM) and cardiovascular disease but also helps to plan management strategies that can reduce the health care burden of society [1]. The prevalence of MetS varies from 10% to 84%, depending on sex, age, race, and ethnicity. The frequency of MetS has been increasing throughout Europe and North America in tandem with increases in overweight, obesity, and diabetes. In Southeast Asia, although body mass index is generally lower than in the West, the frequency of MetS is also rising significantly. The prevalence of MetS in Asia is currently about 31%; in Europe, it is about 30-80% [2]. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) accounts for 4-6% of total hemoglobin and coexists with red blood cells, as it reflects the patient’s blood glucose status during the previous 90 years. HbA1c is an intracellular product (in red blood cells), not affected by sugar intake, and is more stable than blood glucose, as the HbA1c value does not reflect the immediate blood glucose levels and is not affected by the time of blood collection (when the patient is full or fasting), helps to exclude cases of hyperglycemia due to stress [3]. In recent years, HbA1c has been included as one of the criteria for diabetes diagnosis.

Moreover, HbA1c is also an indicator used to diagnose pre-diabetes. According to Park et al. [4], HbA1c can predict cardiovascular events in people without diabetes. Studies conducted in the US [5], Europe [6],[7], and China [8], it was documented that HbA1c can be used instead of the fasting blood glucose in the diagnosis of MetS. However, the results of some studies have noted that HbA1c values differ according to ethnic groups [9], [10], [11]. Therefore, we do not yet know whether HbA1c can be added to the fasting blood glucose criterion in the diagnosis of MetS. Stemming from the above situation, we conducted a study on the topic “Use of HbA1c in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome” with the following objectives: (1) Comparing the diagnostic value of HbA1c and fasting blood glucose in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in research subjects. (2) Determine the cut-off point of HbA1c in predicting metabolic syndrome of research subjects.

2. RESEARCH SUBJECTS AND METHODS

2.1. Research subjects

Research subjects were adults who came for a general health check-up at Hue Central Hospital from August 2018 to February 2020,

agreeing to participate in the study and not having the exclusion criteria. Diagnosis of metabolic syndrome is based on the harmonized criteria of IDF, NHLBI, AHA, WHF, IAS, IASO in 2009 [12] when at least 3 of the following 5 components are present: – Elevated waist circumference (in Asian): WC ≥ 90 cm in male; ≥ 80 cm in female. – Elevated triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL (≥ 1.7 mmol/L) or treated for hypertriglyceridemia. – Reduced HDL-Cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) in male; < 50 mg/dL (< 1.29 mmol/L) in female,

or being treat for reduce HDL-Cholesterol. – Elevated blood pressure: BP 130 mmHg and/or 85 mmHg or being treated for hypertension. – Elevated fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL (≥ 5.6 mmol/L) or diagnosed with type 2 Diabetes.

Exclusion criteria: Through clinical examination combined with disease history, medical history, and based on health records, we excluded the following subjects: Subjects who did not agree to participate in the study, pregnant women, patients with acute diseases, malignancies, autoimmune diseases, subjects with chronic diseases (cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, blood diseases, long-term corticosteroid use > 1 month, and diabetes), subjects with abdominal, thoracic and spinal malformation, subjects unable to stand on their own, subjects with severe dementia. Diagnostic model of metabolic syndrome: In this study, we built 3 models to diagnose metabolic syndrome:

– Model 1: Diagnosis of MetS based on IDF (2009).

– Model 2: Diagnosis of MetS based on IDF (2009) but using HbA1c criteria instead of plasma glucose criteria.

– Model 3: Diagnosis of MetS based on IDF (2009), combined with HbA1c criteria.

The level of HbA1c and the fasting plasma glucose for MetS was set at ≥ 5.7%. This is also the lower limit of HbA1c in the diagnosis of prediabetes, similar to the criterion of hyperglycemia ≥ 5.6 mmol/L in the diagnosis of MetS and the lower limit of fasting hyperglycemia in the diagnosis of prediabetes. [13]

Sample size: Using the formula to calculate sample size:

![]() corresponding to a 95% confidence level; p: The prevalence of MetS based on the research results of Sang Hyun Park et al was 8.5% [4], so we chose p = 0.085; d: Absolute error is 0.06; n: Number of people participating in the study; Calculate the

corresponding to a 95% confidence level; p: The prevalence of MetS based on the research results of Sang Hyun Park et al was 8.5% [4], so we chose p = 0.085; d: Absolute error is 0.06; n: Number of people participating in the study; Calculate the

minimum sample size n = 83.

We proceeded with convenience sampling until we reached a sufficient number of sample sizes. In this study, we conducted the research on 338 subjects.

2.2. Research methods:

Using a cross-sectional descriptive study method on 338 adult subjects without diabetes who came for health check-ups at Hue Central Hospital. MetS were diagnosed according to harmonized criteria IDF, NHLBI, AHA, WHF, IAS, IASO 2009. Waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and biochemistry indicators (triglyceride, HDLCholesterol, fasting plasma glucose, and HbA1c) were determined. The threshold value of HbA1c to predict based on ROC analysis.

2.3. Data process and analysis:

The statistical method uses statistical software SPSS version 25.0 and Medcalc version 19.1.3.

3. RESEARCH RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of research subjects

The average age in our study was 48.39 ± 12.84, of which 168 male subjects accounted for 49.7%, and 170 female subjects accounted for 50.3%.

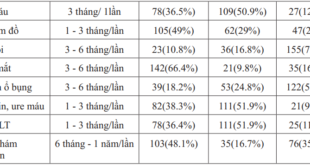

Among research subjects, the proportion of elevated WC was 46.2%, elevated triglyceride was 50.6%, reduced HDL-C was 48.5%,

elevated BP 28.4%, elevated FPG was 37.6%. The mean value of HbA1c was 5.61 ± 0.57(%).

3.2. Value of criteria HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in study subjects

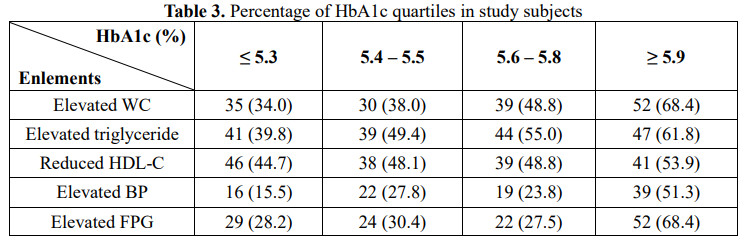

In the study subjects, the proportion of elements of MetS tends to increase gradually from the first quartile to the fourth quartile of HbA1c (Table 3).

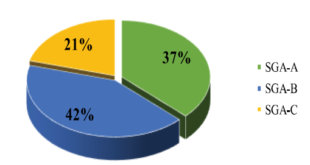

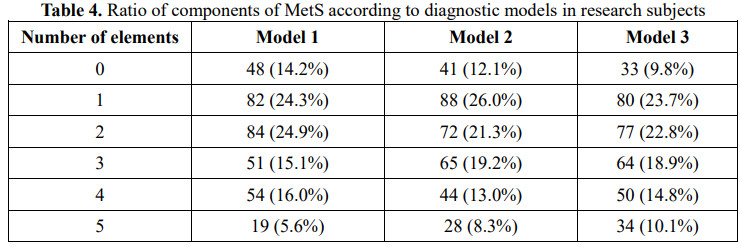

In the study subjects, the rate of having three or more elements in model 2 was higher than in model 1. In model 3, it helped to diagnose more MetS than using each single criterion (Table 4).

Model 1: MetS according to plasma glucose; Model 2: MetS according to HbA1c; Model 3: MetS according to plasma glucose + HbA1c.

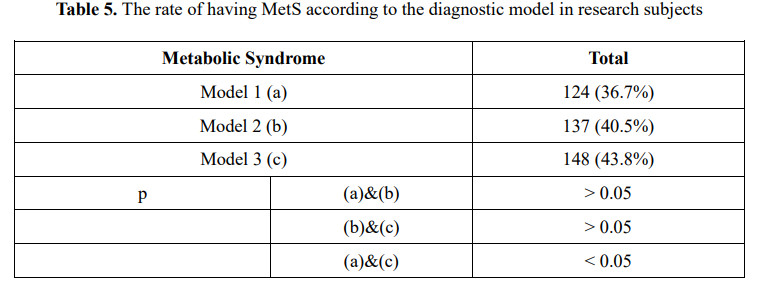

In the study subjects, model 3 had 148 subjects with MetS, accounting for 43.8%, higher than model 1 with 124 subjects with MetS, accounting for 36.7%, which was statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

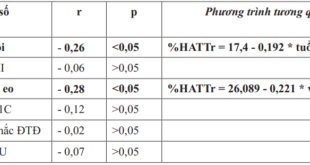

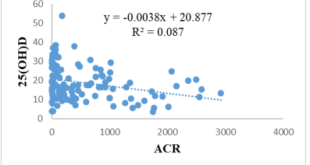

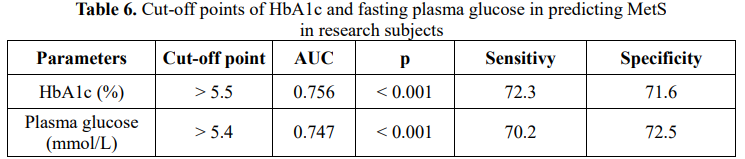

In study subjects, HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose were both valuable in predicting MetS with AUC > 0.7, p < 0.001 (Table 6).

4. DISCUSSION

The results of our study included 168 males, accounting for 49.7%, 170 females accounting for 50.3%, and the average age was 49.90 ± 11.38. The rate of elevated waist circumference was 46.2%, elevated triglycerides were 50.6%, reduced HDL-C was 48.5%, high BP was 28.4%, and elevated FPG was 37.6%. The mean value of HbA1c was 5.61 ± 0.57 (%).

In other countries, Herningtyas et al. noted that the elements of metabolic syndrome in Indonesians accounted for the highest proportion, which was the reduced HDL-C (66.41%), followed by elevated BP (64.45%) and elevated WC (43.21%) [14]. Research results of Lan Y et al. noted that the most common elements were hypertension (24.52%), followed by dyslipidemia (24%), body mass index ≥ 25.0 (22.07%), and elevated plasma glucose (19.25%) [15].

Therefore, each country has its different model of the prevalence of each component of MetS; it is challenging to have a standard model framed for the population due to significant differences in cultural, demographic, and socioeconomic factors.

Our research results show that the proportion of elements of MetS tends to increase gradually from the first quartile to the fourth quartile of HbA1c. The proportion of 3 or more elements in model 2 was higher than in model 1. In model 3, it helped to diagnose MetS more than using each element alone. Model 3 has 148 subjects having MetS, accounting for 43.8%, which is higher than model 1 with 124 subjects with MetS, accounting for 36.7% (p < 0.05).

The HbA1c test was used to assess blood glucose monitor. The test provided an average of blood glucose levels over the past 90 days and was also used to diagnose diabetes and prediabetes [16]. Osei K et al. reported that the HbA1c of African-American subjects with HbA1c levels between 5.7 and 6.4% had an increased number of elements of MetS, which reinforced the influence of HbA1c in the diagnosis of MetS. [17].

In another study in Korean adults without diabetes, Sung K.C and E.J. Rhee noted that insulin resistance, the underlying mechanism for the etiology of metabolic syndrome, elevated with increasing quartiles of HbA1c [18]. In this research, we compared the diagnosis of MetS using HbA1c or fasting plasma glucose as a plasma glucose criterion in subjects without a history of diabetes having medical check-ups.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose as plasma glucose criteria of MetS

among subjects without diabetes having medical check-ups in Vietnam.

To evaluate the relationship between HbA1c and elements of MetS, we assessed the rate of elements of MetS according to the HbA1c quartile. We observed that the proportion of elements of HbA1c tended to increase gradually from the first quartile to the fourth quartile of HbA1c.

This suggested that elevated HbA1c can lead to metabolic disorders consistent with the results of previous studies [5], [6], [7], [17]. In this study, we also recorded that more subjects had 3 or more elements in model 2 than in model 1. In model 3, it helped diagnose MetS more than using a single component. This finding may be due to the close association between HbA1c and components of MetS relative to fasting plasma glucose.

Similarly, a cross-sectional study by Saravia et al. in 3200 men without diabetes found that HbA1c was strongly associated with waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, and reduced HDL-C compared with fasting plasma glucose [19].

Succurro et al., in a cohort of Caucasians without diabetes, also found that HbA1c was better correlated with visceral fat, HDL-C, and

triglycerides when compared with fasting plasma glucose [6].

These findings suggested that the inclusion of HbA1c during MetS screening may contribute to the identification of more subjects at risk of cardiovascular events among subjects without diabetes.

The results of our study recorded that model 3 had 148 subjects with MetS, accounting for 43.8%, higher than model 1, which had 124 subjects with MetS, accounting for 36.7% (p < 0.05)—similarly, the research results of Siu P.M and Q.S. Yuen [1], Park et al. [4], Cavero-Redondo et al. [20], and Sun X et al. [8] all support the feasibility of using HbA1c along with fasting plasma glucose as an increased plasma glucose criterion in the diagnosis of MetS.

Our research showed that HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose were valuable in predicting MetS with AUC > 0.7, p < 0.001. Several studies have investigated the usefulness of HbA1c as a predictor of metabolic syndrome. Park et al. analyzed HbA1c in 7,307 subjects without diabetes in a health screening program as they recorded that an HbA1c > 5.65% could be used as a diagnostic criterion for MetS [4].

According to Annani-Akollor M.E et al. [21], using the HbA1c criterion along with fasting plasma glucose in the screening for MetS improved the ability to identify more subjects with MetS.

They would otherwise be missed when the diagnosis of MetS was based on fasting plasma glucose only. Recent studies have documented that HbA1c, from 5.45% to 5.65%, was a predicting element for MetS in subjects without diabetes [22], [18].

Several studies have also investigated the association between HbA1c and metabolic syndrome. Research results of Saravia et al.

[19] noted that HbA1c was closely associated with elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, and reduced HDL-C.

Similarly, Succurro et al. also reported a better correlation of HbA1c with parameters of visceral fat, HDL-C, and triglycerides [6]. Kim H et al. [23] noted that an increase in HbA1c was significantly associated with the increase in body mass index, rate of myocardial infarction, fasting plasma glucose, blood pressure, and total cholesterol; moreover, the incidence of MetS in subjects with HbA1c above 5.6% was 14 times higher than in subjects with HbA1c below 5.2%.

5. CONCLUSION

According to our result, the potential role of HbA1c that should be considering adding to the criteria of fasting plasma glucose in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome.

REFERENCES

1. Siu, P.M. and Q.S. Yuen, Supplementary use of HbA1c as hyperglycemic criterion to detect metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr, 2014. 6(1):119.

2. Gupta, A., et al., Obesity is Independently Associated With Increased Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer-related Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Clin Oncol, 2018. 41(9):874-881.

3. Leow, M.K., Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c): Clinical Applications of a Mathematical Concept. Acta Inform Med, 2016. 24(4):233-238.

4. Park, S., et al., GHb is a better predictor of cardiovascular disease than fasting or postchallenge plasma glucose in women without diabetes. The Rancho Bernardo Study. Diabetes Care, 1996. 19(5):450-6.

5. Ong, K.L., et al., Using glycosylated hemoglobin to define the metabolic syndrome in United States adults. Diabetes Care, 2010. 33(8):1856-8.

6. Succurro, E., et al., Usefulness of hemoglobin A1c as a criterion to define the metabolic syndrome in a cohort of italian nondiabetic white subjects. Am J Cardiol, 2011. 107(11):1650-5.

7. Bernal-Lopez, M.R., et al., Why not use the HbA1c as a criterion of dysglycemia in the new definition of the metabolic syndrome? Impact of the new criteria in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in a Mediterranean urban population from Southern Europe (IMAP study. Multidisciplinary intervention in primary care). Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2011. 93(2):e57-e60.

8. Sun, X., et al., Impact of HbA1c criterion on the definition of glycemic component of the metabolic syndrome: the China health and nutrition survey 2009. BMC Public Health, 2013. 13:1045.

9. Herman, W.H., et al., Differences in A1C by race and ethnicity among patients with impaired glucose tolerance in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care, 2007. 30(10):2453-7.

10. Herman, W.H. and R.M. Cohen, Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose: implications for the diagnosis of diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2012. 97(4):1067-72.

11. Adams, A.S., et al., Medication adherence and racial differences in A1C control. Diabetes Care, 2008. 31(5):916-21.

12. Alberti, K.G., et al., Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation, 2009. 120(16):1640-5.

13. American Diabetes Association, 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes2019. Diabetes Care, 2019. 42(Suppl1): S13-s28

14. Herningtyas, E.H. and T.S. Ng, Prevalence and distribution of metabolic syndrome and its components among provinces and ethnic groups in Indonesia. BMC Public Health, 2019. 19(1):377.

15. Lan, Y., et al., Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in China: An up-dated crosssectional study. PLoS One, 2018. 13(4):e0196012.

16. Gilstrap, L.G., et al., Association Between Clinical Practice Group Adherence to Quality Measures and Adverse Outcomes Among Adult Patients With Diabetes. JAMA Netw Open, 2019. 2(8):e199139.

17. Osei, K., et al., Is glycosylated hemoglobin A1c a surrogate for metabolic syndrome in nondiabetic, first-degree relatives of African-American patients with type 2 diabetes? J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2003. 88(10):4596-601.

18. Sung, K.C. and E.J. Rhee, Glycated haemoglobin as a predictor for metabolic syndrome in non-diabetic Korean adults. Diabet Med, 2007. 24(8):848-54.

19. Saravia, G., et al., Glycated Hemoglobin, Fasting Insulin and the Metabolic Syndrome in Males. Cross-Sectional Analyses of the Aragon Workers’ Health Study Baseline. PLoS One, 2015. 10(8):e0132244.

20. Cavero-Redondo, I., et al., Metabolic Syndrome Including Glycated Hemoglobin A1c in Adults: Is It Time to Change? J Clin Med, 2019. 8(12).

21. Annani-Akollor, M.E., et al., Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and the comparison of fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c as the glycemic criterion for MetS definition in non-diabetic population in Ghana. Diabetol Metab Syndr, 2019. 11:26.

22. Park, S.H., et al., Usefulness of glycated hemoglobin as diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome. J Korean Med Sci, 2012. 27(9):1057-61.

23. Kim, H., et al., Correlation between Hemoglobin A1c and Metabolic Syndrome in Adults without Diabetes under 60 Years of Age. Korean Journal of Family Practice, 2017. 7(1):60-65.

Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam

Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam