CARDIO-METABOLIC RISK FACTORS IN VIETNAMESE MEN

ON VEGETARIAN DIET

Nguyen Hai Thuy, Le Van Chi, Nguyen Thi Kim Anh,

Nguyen Hai Quy Tram, Nguyen Hai Ngoc Minh.

Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy

ABSTRACT

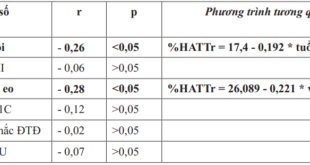

Background: Numerous cross-sectional studies have shown that vegetarian diet has beneficial effects on the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. However, whether long-term vegetarian diet might be cardiometabolic risk factors are still unclear. Objectives: To investigate the influence of vegetarian diet on cardiometabolic risk factors, and more importantly on plasma levels of testosterone and leptin among vegetarian males in Vietnam. Methods: 93 Vietnamese males (age 16-78 years) with duration of vegetarian diet ranged 5-65 years, were screened for cardiometabolic risk factors including BMI, WC, blood pressure, fasting glucose, HbA1c, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, HOMA-%B, lipid profile, serum levels of hsCRP, Leptin and Testosterone, and the control group was 86 non-vegetarian men (age 17-72 years). Results: The vegetarian group had lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome compared to the non-vegetarian one (12.9% vs 24.4%, p <0.01), lower serum hsCRP concentration (0.85 ±0.94 vs 4.21 ±5.73 mg/l, p < 0.05), lower serum total cholestrol (4.05 ± 0.92 vs 5.21 ± 1.21 mmol/l, p<0,01), lower LDL.C (2.07 ± 0.72 vs 3.39 ± 1.09 mmol/l, p<0.01), lower non-HDL.C (2.88 ± 0.96 vs 4.04 ±118 mmol/l, p<0.01), lower TC/HDL.C ratio (3.62 ± 1.18 vs 4.67 ± 1.33, p<0.01), and lower LDL.C/HDL.C ratio (1.86 ± 0.81 vs 3.06 ± 1.15, p<0.05), respectively. In contrast, serum Testosterone level was higher in vegetarian males (6.37 ±1.78 vs 5.29 ± 2.38 ng/ml, p=0.008). Between the vegetarian and non-vegetarian men, there were no differences in BMI (22.13 ± 3.59 vs 22.56 ± 2.88, p>0.05 ),in WC (77.61 ±8.62 vs 79.76± 7.14 cm, p>0.05), in SBP (116.88±12.20 vs 122.31±13.77 mmHg, p>0.05),in DBP (77.84 ±8.77 vs 77.76±10.00 mmHg, p >0.05), in fasting glucose ( 4.65 ± 0.53 vs 5.05 ± 0.68 mmol/l , p > 0.05), in fasting insulin (5.85 ± 4.53 vs 5.93 ± 3.2 µU/ml, p>0.05), in HOMA-IR (1.25 ±1.18 vs 1.3 ±0,83, p>0.05), in TG (1.81 ± 1.04 vs 2.03 ± 1.16 mmol/l, p >0.05), in HDL.C (1.17 ± 0.25 vs 1.17 ± 0.31 mmol/l , p >0,05), and in TG/HDL.C (1.71 ± 1.26 vs 1.88 ± 1.25, p >0.05), respectively. Compared to non-vegetarian group, the vegetarian one had lower serum concentration of leptin (1.46± 1.48 vs 3.16 ±2.95 ng/ml, p < 0.01), higher serum testosterone level ( 6.37 ±1.78 vs 5.29 ± 2.38, p=0.008) but higher HbA1c level (5.51± 0.71 vs 4.96 ±0.69%, p < 0.01) and higher prevalence of prediabetes based on HbA1c ≥ 5.7 % (35,5% vs 5.8%, p < 0.01), respectively. There was a correlation between HbA1c level with age, duration of vegetarian diet, BMI, WC, TG, leptin and testosterone levels; in which the vegetarian duration was identified as an independent risk factor of hyperglycemia by multiple regression analysis. The vegetarian duration cut-off point for prediabetes analyzed by ROC was 21 years and the age cut off point for prediabetes was 35 years old, which was younger than in non vegetarians (46 years old). Conclusions: A decrease in multiple cardiometabolic risk factors such as BMI, blood pressure and lipid profile was associated with vegetarian diet. However, long-term vegetarian diet could cause hyperglycemia and hypoleptinemia. Those effects appeared to be correlated with the vegetarian duration (more than 21 years).

Keywords: vegetarian diet, duration of vegetarian diet, cardiometabolic risk factors.

Main correspondence: Nguyen Hai Thuy

Submission date: 1st August 2018

Revised date: 18th August 2018

Acceptance date: 31th August 2018

1.INTRODUCTION

Cardio Metabolic Syndrome (CMS), also known as insulin resistance syndrome or metabolic syndrome X, is a combination of metabolic disorders or risk factors that essentially includes a combination of diabetes mellitus, systemic arterial hypertension, central obesity and dyslipidemia. Studies have shown a strong link between CMS and increased prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. Vegetarian diets exclude all animal flesh. Varieties of vegetarianism include vegan, raw vegan, ovovegetarian, lactovegetarian, lacto-ovovegetarian, and pescovegetarian.

Each type of vegetarianism excludes or includes certain foods. In recent years, adopting a vegetarian diet has become increasingly popular.

Numerous cross-sectional studies have shown that vegetarian diet has beneficial effects on the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. However, whether long-term vegetarian diet might be cardiometabolic risk factors are still unclear.

2. OBJECTIVES

Investigate the influence of vegetarian diet on cardiometabolic risk factors, and more importantly on plasma levels of testosterone and leptin among vegetarian males in Vietnam.

3. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

93 Vietnamese males (age 16-78 years) with duration of vegetarian diet ranged 5-65 years, were screened for cardiometabolic risk factors including BMI, WC, arterial blood pressure, fasting glucose, HbA1c, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, HOMA-%B lipid profile, serum levels of hsCRP, Leptin and Testosterone. Control group compose 86 non-vegetarian men (age 17-72 years).

4. RESULTS OF STUDY

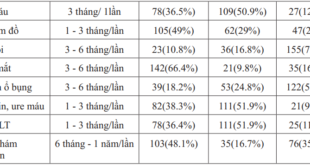

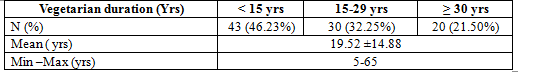

Table 1. Duration of vegetarian diet

Mean duration of vegetarian diet was 19.52 ±14.88 yrs, in which < 15 yrs and ≥ 30 yrs were 46,23% and 21,5% respectively.

Mean duration of vegetarian diet was 19.52 ±14.88 yrs, in which < 15 yrs and ≥ 30 yrs were 46,23% and 21,5% respectively.

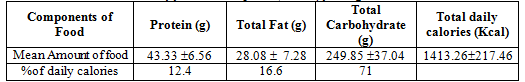

Table 2. Daily food consumption (in kcal) for vegetarian men

71% of total daily calories be supplied by carbohydrate

71% of total daily calories be supplied by carbohydrate

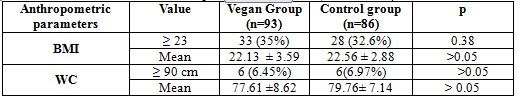

Table 3. Anthropometric parameters (BMI and WC)

In our study, there was not significantly different between the vegetarian group with control group in the proportion of overweight (35% vs 32,6%, p >0,05), in the mean BMI (22.13 ± 3.59 vs 22.56 ± 2.88, p>0.05 ), in the proportion of android obesity (6.45% vs 6.97%, p >0,05) and in the mean WC (77.61 ±8.62 vs 79.76± 7.14 cm, p>0.05)

In our study, there was not significantly different between the vegetarian group with control group in the proportion of overweight (35% vs 32,6%, p >0,05), in the mean BMI (22.13 ± 3.59 vs 22.56 ± 2.88, p>0.05 ), in the proportion of android obesity (6.45% vs 6.97%, p >0,05) and in the mean WC (77.61 ±8.62 vs 79.76± 7.14 cm, p>0.05)

Christopher L Melby et al (1994) showed that vegetarians had a lower waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) compared with the non-vegetarians.[1]. EA Spencer et al (2003) found that Age-adjusted mean BMI was significantly different between the four diet groups, being highest in the meat-eaters (24.41 kg/m2 in men, 23.52 kg/m2 in women) and lowest in the vegans (22.49 kg/m2 in men, 21.98 kg/m2 in women). Vegetarians and especially vegans had lower BMI than meat-eaters[2].

PK Newby et al (2005). showed that prevalence of overweight or obesity (BMI ≥_ 25) was 40% among omnivores, 29% among both semi-vegetarians and vegans, and 25% among lacto-vegetarians[3]. Sutapa Agrawal et al (2014) showed that mean BMI was lowest in pesco-vegetarians (20.3 kg/m2) and vegans (20.5 kg/m2) and highest in lacto-ovo vegetarian (21.0 kg/m2) and lacto-vegetarian (21.2 kg/m2) diets [4].

Mi-Hyun Kim et al (2015). Study a group of Korean postmenopausal vegetarian women (n = 54), who maintained a semi-vegetarian diet for over 20 years and a group of non-vegetarian controls.

The vegetarians showed significantly lower body weight (p < 0.01), BMI (p < 0.001), percentage (%) of body fat (p <0.001) than the non vegetarians[5].

Ashwini et al (2016) found that vegetarian diet have a more favourable anthropometry, with lower weight, BMI, WHR when compared to non-vegetarians[6].

Identifying young adults with unfavourable metabolic profile and adapting suitable dietary modifications tends to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease particularly in developing countries.

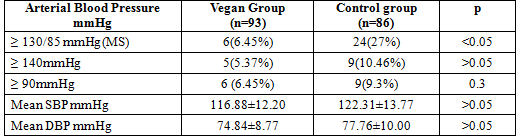

Table 4. Arterial Blood Pressure of study groups

In our study, the mean SBP in vegan group was not significantly higher than that in control group (116.88±12.20 vs 122.31±13.77 mmHg, p>0.05) and the average DBP in vegan group was not lower significantly than that in control group(74.84 ±8.77 vs 77.76±10.00 mmHg, p >0.05). The proportion of high SBP in vegan group is not significantly lower than that in control group (5,37% vs 10,46 %, p >0.05) and the percentage of high DBP in vegan group was significantly not higher than that in control group (6,45% vs 9,3 %, p>0.05). But the proportion of vegetarian subjects with arterial blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg (Metabolic Syndrome) in vegan group was significantly lower than that in control group (6.45 vs 27%, p<0.05)

In our study, the mean SBP in vegan group was not significantly higher than that in control group (116.88±12.20 vs 122.31±13.77 mmHg, p>0.05) and the average DBP in vegan group was not lower significantly than that in control group(74.84 ±8.77 vs 77.76±10.00 mmHg, p >0.05). The proportion of high SBP in vegan group is not significantly lower than that in control group (5,37% vs 10,46 %, p >0.05) and the percentage of high DBP in vegan group was significantly not higher than that in control group (6,45% vs 9,3 %, p>0.05). But the proportion of vegetarian subjects with arterial blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg (Metabolic Syndrome) in vegan group was significantly lower than that in control group (6.45 vs 27%, p<0.05)

Christopher L Melby and et al (1994). Showed that only 16% of the vegetarians were confirmed to be hypertensive compared with 35.7% of the semi-vegetarians and 31.1% of the nonvegetarians. Among African-American 2DM, a vegetarian diet was associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk factors than is an omnivorous diet.[1].

Krithiga Shridhar1 et al (2014) evaluated the association between vegetarian diets (chosen by 35%) and CVD risk factors across four regions of India.

Results: Vegetarians also had decreases in SBP (ABP =20.9 mmHg (95% CI: 21.9 to 0.08), p>0.05) when compared to nonvegetarians[7].

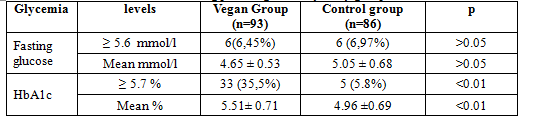

Table 5. Fasting plasma glucose of study groups

Fasting plasma glucose in vegan group was not lower than that in non vegan group (4.65 ± 0.53 vs 5.05 ± 0.68 mmol/l , p > 0.05) and percentage of FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/l was not difference between 2 groups (6,45% vs 6,97%, p > 0.05), but concentration of HbA1c in vegan group was signficantly higher than that in non vegan group (5.51± 0.71 vs 4.96 ±0.69%, p < 0.01), and percenage of HbA1c ≥ 5.7 % in vegan group was higher than that in non vegan group (35,5 % vs 5.8%, p < 0.01).

Fasting plasma glucose in vegan group was not lower than that in non vegan group (4.65 ± 0.53 vs 5.05 ± 0.68 mmol/l , p > 0.05) and percentage of FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/l was not difference between 2 groups (6,45% vs 6,97%, p > 0.05), but concentration of HbA1c in vegan group was signficantly higher than that in non vegan group (5.51± 0.71 vs 4.96 ±0.69%, p < 0.01), and percenage of HbA1c ≥ 5.7 % in vegan group was higher than that in non vegan group (35,5 % vs 5.8%, p < 0.01).

In our study, the proportion of hyperglycemia (based on fasting plasma glucose) was not diference between 2 groups (6,45 % vs 6,97 %, p >0.05). The mean fasting plasma glucose was not difference between 2 groups (4.65 ± 0.53 vs 5.05 ± 0.68 mmol/l , p > 0.05).

Explication for prevalence of hyperglycemia in vegan group, in previous study we evaluated the carbohydrate counting in the same population in this region. We found that the carbohydrate consuming daily more than 70% of total energy.

Yoko Yokoyama et al (2014) of 477 studies identified, six met the inclusion criteria (n=255, mean age 42.5 years). Consumption of vegetarian diets was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c [−0.39 percentage point; 95% confidence interval (CI), −0.62 to −0.15; P=0.001; I 2=3.0; P for heterogeneity =0.389], and a non-significant reduction in fasting blood glucose concentration (−0.36 mmol/L; 95% CI, −1.04 to 0.32; P=0.301; I2=0; P for heterogeneity =0.710), compared with consumption of comparator diets. Conclusions: Consumption of vegetarian diets is associated with improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetes[8]. Shu-Yu Yang, et al (2011)” Omnivores had significantly higher fasting blood glucose than that of vegetarians.[9]. Mi-Hyun Kim et al (2015) The present study was conducted to compare insulin resistance between Korean postmenopausal longterm semi-vegetarians and non-vegetarians.

Subjects of this study belonged to either a group of postmenopausal vegetarian women (n = 54), who maintained a semi-vegetarian diet for over 20 years or a group of non-vegetarian controls.

The vegetarians showed significantly lower glucose (p < 0.001) than that of the non-vegetarians (p<0.01) after adjustment for the % of body fat[5].

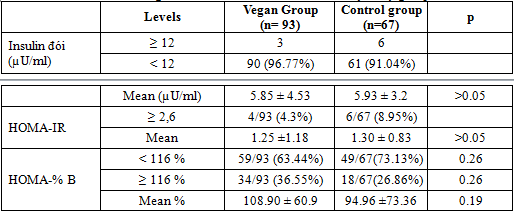

Table 6. Fasting Insulin, HOMA-IR and HOMA-%B of study groups

The proportion of Fasting insulin ≥12 µU/ml in vegan group was 7,6% but not cas in control group. Mean fasting insulinemia in vegan group was significantly higher than that in control group (6,9 ± 4,3 vs5.55 ± 2.13 µU/ml , p=0.0118).

The proportion of Fasting insulin ≥12 µU/ml in vegan group was 7,6% but not cas in control group. Mean fasting insulinemia in vegan group was significantly higher than that in control group (6,9 ± 4,3 vs5.55 ± 2.13 µU/ml , p=0.0118).

The percentage of HOMA-IR ≥ 2,6 in Vegan group is significantly higher than control group (9,7% vs 1,5%, p<0,05) and the mean HOMA-IR index in vegan group is higher than in control group (1,67±1,62 vs 1,16 ± 0,55, p< 0,05)

The proportion of HOMA-%B ≥ 116% in Vegan group is significantly not higher than control group ( 36,55% vs 26,86%, p >0,05) and the mean HOMA-% B in vegan group was not significantly diferent between two groups (108.90 ± 60.9 vs 94.96 ±73.36%, p>0.05).

Maelán Fontes‑Villalba et al (2016). In a randomised, open‑label, cross‑over study, 13 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to eat a Palaeolithic diet based on lean meat, fish, fruits, vegetables, root vegetables, eggs and nuts, or a diabetes diet designed in accordan ce with current diabetes dietary guidelines during two consecutive 3‑month periods. Over a 3‑month study period, a Palaeolithic diet did not change fasting levels of insulin compared to the cur‑rently recommended diabetes diet [10]. Shu-Yu Yang, 2011. Omnivores had significantly higher fasting blood glucose than that of vegetarians. However, there were no differences in fasting insulin and HOMA-IR between the two groups.[9]

Mi-Hyun Kim, et al (2015); The HOMA-IR of the vegetarians was significantly lower than that of the non-vegetarians (p < 0.01) after adjustment for the % of body fat. A long-term vegetarian diet might be related to lower insulin resistance independent of the % of body fat in postmenopausal women.[5].

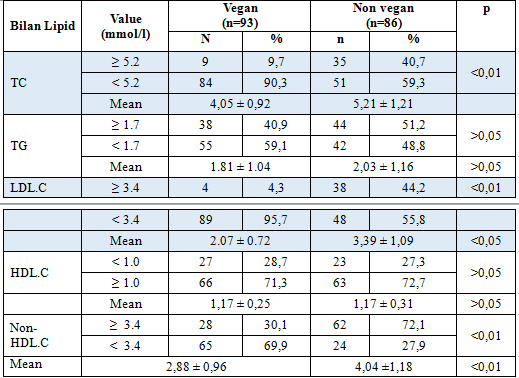

Table 7. Lipid profile of study groups

In our study, the proportion of TC (≥ 5,2mmol/l) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group ( 9,7% vs 40,7%, p < 0,01). The mean TC in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (4,05 ± 0,92 vs 5,21 ± 1,21 mmol/l, p<0,01).Percentage of LDL.C (≥ 3,4 mmol/l) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (4,3% vs 44,2%, p<0,01), and the mean LDL.C in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (2.07 ± 0.72 vs 3,39 ± 1,09 mmol/l, p<0,01).The prevalence of TG (≥ 1,7 mmol/l) in vegan group was not significantly lower than in control group (40,9 vs 51,2%p >0,05), and the mean TG in vegan group is not significantly lower than in control group (1.81 ± 1.04 vs 2,03 ± 1,16 mmol/l, p >0,05).The Proportion of HDL.C (<1,3 mmol/l) in vegan group was not significantly higher than in control group (28,7 vs 27,3%), p >0,05) and the mean HDL.C in vegan group is significantly lower than in control group (1,17 ± 0,25 vs 1,17 ± 0,31 , p >0,05).The percentage of non HDL.C (≥3.4 mmol/l) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (30,1 % vs 72,1%,p<0,01) and the mean Non- HDL.C in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (2,88 ± 0,96 vs 4,04 ±1,18 mmol/l, p<0,01).

In our study, the proportion of TC (≥ 5,2mmol/l) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group ( 9,7% vs 40,7%, p < 0,01). The mean TC in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (4,05 ± 0,92 vs 5,21 ± 1,21 mmol/l, p<0,01).Percentage of LDL.C (≥ 3,4 mmol/l) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (4,3% vs 44,2%, p<0,01), and the mean LDL.C in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (2.07 ± 0.72 vs 3,39 ± 1,09 mmol/l, p<0,01).The prevalence of TG (≥ 1,7 mmol/l) in vegan group was not significantly lower than in control group (40,9 vs 51,2%p >0,05), and the mean TG in vegan group is not significantly lower than in control group (1.81 ± 1.04 vs 2,03 ± 1,16 mmol/l, p >0,05).The Proportion of HDL.C (<1,3 mmol/l) in vegan group was not significantly higher than in control group (28,7 vs 27,3%), p >0,05) and the mean HDL.C in vegan group is significantly lower than in control group (1,17 ± 0,25 vs 1,17 ± 0,31 , p >0,05).The percentage of non HDL.C (≥3.4 mmol/l) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (30,1 % vs 72,1%,p<0,01) and the mean Non- HDL.C in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (2,88 ± 0,96 vs 4,04 ±1,18 mmol/l, p<0,01).

Table 8. Atherogenic index of study group

In our study, the proportion of TC/HDL (≥ 4) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (28% vs 65,1%,, p<0,01) and the mean TC/HDL in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (3,62 ± 1,18 vs 4,67 ± 1,33, p<0,01). The proportion of LDL.C/HDL (≥ 2.3) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (26,9 % vs 72,1, p <0,01) and the mean LDL.C/HDL in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (1,86 ± 0,81 vs 3,06 ± 1,15, p <0.01).

In our study, the proportion of TC/HDL (≥ 4) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (28% vs 65,1%,, p<0,01) and the mean TC/HDL in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (3,62 ± 1,18 vs 4,67 ± 1,33, p<0,01). The proportion of LDL.C/HDL (≥ 2.3) in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (26,9 % vs 72,1, p <0,01) and the mean LDL.C/HDL in vegan group was significantly lower than in control group (1,86 ± 0,81 vs 3,06 ± 1,15, p <0.01).

The proportion of TG/HDL.C in vegan group was not significantly lower than in control group (23,7% vs 25,6%, p>0,05) and the mean TG/HDL was not difference between in 2 group (1,71 ± 1,26 vs 1,88 ± 1,25, p >0,05).

Christopher L Melby et al (1994) the VEGs had significantly lower concentrations of serum total cholesterol (STC), LDL-C, triglycerides, STC/HDL-C, and LDL-C/HDL-C than the NONVEGs. The SEMIVEGs had lipid values intermediate to the VEG and NONVEG groups. Among African-American 2DM, a vegetarian diet was associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk factors than is an omnivorous diet [7]. Ambroszkiewicz J et al (2004) examined 22 vegetarians and 13 omnivores in age 2-10 years. Average daily dietary energy intake and the percentage of energy from protein, fat and carbohydrates were similar for both groups of children. They observed that in vegetarian diet there is a high rate of fiber nearly twice as high as in omnivorous diet. Vegetarians had lower total cholesterol and HDL- and LDL-cholesterol concentrations than children on traditional mixed diet. There is no significant differences in triglyceride concentration between studied groups [11]. Simone Grigoletto De Biase et al (2005). Vegetarian diet was associated to lower levels of TG, TC and LDL as compared to the diet of omnivores.[12]

Neal D. Barnard and et al (2006). Individuals with type 2 diabetes (n _ 99) were randomly assigned to a low-fat vegan diet (n _ 49) or a diet following the American. Among those who did not change lipid-lowering medications, LDL cholesterol fell 21.2% in the vegan group and 10.7% in the ADA group (P _ 0.02)[14]. Yee-Wen Huang and et al (2014): a cross-sectional study of pre and postmenopausal women .Vegan diet was associated with reduced HDL-C level. Because of its effects on lowering HDL-C and LDL-C, ovo-lacto vegetarian diet may be more appropriate for premenopausal women[15]. Pranay Gandhi and et al (2014). A Study of Vegetarian Diet and Cholesterol and Triglycerides Levelsa Results: Significant difference was reported for TC, LDL and TG levels among the samples. Higher levels were reported by omnivores, with decreased levels for vegetarians as animal products were restricted, with lowest levels having been reported by vegans. Mean and standard deviation for TC were 208.09 ± 49.09 mg/dl in the group of omnivores, and 141.06 ± 30.56 mg/dl in the group of vegans (p < 0.001). Conclusion: Vegetarian diet was associated to lower levels of TG, TC and LDL as compared to the diet of omnivores [16].

Manish Verma1*and et al (2015). Conclusions: this systematic review and meta-analysis provides evidence that vegetarian diets effectively lower blood concentrations of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Such diets could be a useful nonpharmaceutical means of managing dyslipidemia, especially[17]. Shu-Yu Yang, (2011). Compared to the omnivores, the levels of triglyceride, total cholesterol, HDL-Cholesterol, LDL-Cholesterol, ApoA1, ApoB were significantly reduced in vegetarians[10]. Christopher L Melby et al (1994). Study blood lipids among vegetarian, semivegetarian, and nonvegetarian African Americans. VEGs had a lower dietary intakes of saturated fat, and cholesterol compared with the NONVEGS. Independent of differences in WHR, the VEGs had significantly lower concentrations of serum total cholesterol (STC), LDL-C, triglycerides, STC/HDL-C, and LDL-C/HDL-C than the NONVEGs. The SEMIVEGs had lipid values intermediate to the VEG and NONVEG groups. Among African-American 5DM, a vegetarian diet was associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk factors than is an omnivorous diet[7].

Sumon Kumar Das et al (2012). To examine the association between consumption of vegetable-based diets and lipid profile of aged vegetarians in rural Bangladesh. Results: The mean age of the vegetarians and non-vegetarians were 58 and 57 years respectively with normal kidney and liver function. The vegetarians had significantly lower mean serum. Total Cholesterol (TC) [mean difference (95% CI)] [-0.40 (-0.74, -0.06)] and LDL [-0.47 (-0.76, -0.19)] compared to non-vegetarians. They also had lower mean levels of TC: HDL [-0.55 (-0.98, -0.13)] and LDL:HDL [-0.48 (-0.84, -0.13)]. In Pearson’s correlation, consumption of vegetable diet significantly correlated with serum TC, LDL and TC/HDL and LDL/HDL ratios. In multiple regression analysis, age, dietary habit, BMI, FBS, and radial pulse had positive correlation with LDL. Instead of radial pulse, for TC/ HDL ratio, sex correlated along with other factors. Whereas, for LDL/ HDL ratio direct correlation was found with age, dietary habit and BMI. Conclusion: Findings of this study suggest that compared to non-vegetarians, rural Bangladeshi vegetarians had better serum lipid profile[12].

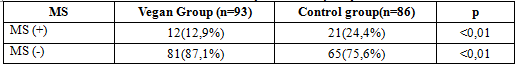

Table 9. Prevalence of MS in study subjects

In our study, the proportion of MS (+) in vegan group was significantly lower than that of control group (12.9% vs 24.4%, p <0.01).

In our study, the proportion of MS (+) in vegan group was significantly lower than that of control group (12.9% vs 24.4%, p <0.01).

NICO S. RIZZO et al (2011) in the Cross-sectional analysis of 773 subjects (mean age 60 years) from the Adventist Health Study 2 was performed. Dietary pattern was derived from a food frequency questionnaire and classified as vegetarian (35%), semi-vegetarian (16%), and nonvegetarian (49%). ANCOVA was used to determine associations between dietary pattern and MRFs (HDL.C, triglycerides, glucose, blood pressure, and waist circumference) while controlling for relevant cofactors. Logistic regression was used in calculating odds ratios (ORs) for MetS. RESULTS-A vegetarian dietary pattern was associated with significantly lower means for all MRFs except HDL.C (P for trend , 0.001 for those factors) and a lower risk of having MetS (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.30–0.64, P , 0.001) when compared with a nonvegetarian dietary pattern. Conclusions-A vegetarian dietary pattern is associated with a more favorable profile of MRFs and a lower risk of MetS. The relationship persists after adjusting for lifestyle and demographic factors[18].

Penghui Shang et al (2011). The design was a retrospective cohort study using secondary data analysis from a Taiwan longitudinal health check-up database provided by MJ Health Screening Center during 1996–2006. The association between MS or MS components and different dietary groups was evaluated using Cox proportional-hazards regression models with adjustment for confounders. Compared with vegans, hazard ratios of MS for nonvegetarians, pescovegetarians, lactovegetarians were 0.75 (95% CI, 0.64, 0.88), 0.68 (95% CI, 0.55, 0.83) and 0.81 (95% CI, 0.67, 0.97) after adjusting for sex, age, education status, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity at work and leisure, respectively. As for MS components, nonvegetarians and pescovegetarians had 0.72 (95% CI, 0.62, 0.84), 0.70 (95% CI, 0.57, 0.84) times risk of developing low HDL-C, while nonvegetarians had 1.16 (95% CI, 1.02, 1.32) times risk of developing high fasting plasma glucose.[19].

Table 10. hsCRP of study groups

The proportion of hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/l in vegan group was significantly lower than that in control group (4,3% vs 62,68%, p < 0,01). There was significantly difference in the mean levels of hsCRP between vegan group and control group (0.85 ±0.94 vs 4.21 ±5.73 mg/l, p < 0.01)

The proportion of hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/l in vegan group was significantly lower than that in control group (4,3% vs 62,68%, p < 0,01). There was significantly difference in the mean levels of hsCRP between vegan group and control group (0.85 ±0.94 vs 4.21 ±5.73 mg/l, p < 0.01)

Chakole SA1 2014 [21]. Compare hsCRPas a cardiovascular risk marker in vegetarian and non-vegetarian groups. Age and gender matched 50 vegetarian and 50 non-vegetarian healthy subjects were selected. It was found that serum hsCRP was significantly lower in vegetarian than non-vegetarian group (0.67+ 0.04 mg/l vs. 1.5 + 0.09 mg/l; p value < 0.0001). It can be concluded that high consumption of plant foods viz. vegetables, fruits and cereals are associated with lower values of hsCRP. This explains the role of vegetarian diet in suppressing the inflammation and thus in reduction in cardiovascular disease risk [20].

Shu-Yu Yang et al (2011) found that there were no differences in levels of C- reactive protein between the two groups of vegetarians Omnivores [9].

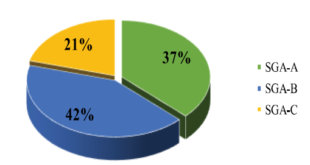

Table 11. Leptin of study groups

![]() The levels of Leptin in vegetarian men was lower than non vegetarian men (1.46± 1.48 vs 3.16 ±2.95 ng/ml, p < 0.01)

The levels of Leptin in vegetarian men was lower than non vegetarian men (1.46± 1.48 vs 3.16 ±2.95 ng/ml, p < 0.01)

Leptin, a hormone from adipose tissue plays a key role in the control of body fat stores and energy expenditure. Higher leptin levels were observed in obese subjects and lower in anorectic patients. Recent studies support that diet may be a factor which influences leptin levelsespecially vegetarian diet, this regimen may play a positive role in reducing risk of several chronic diseases such as diabetes, coronary heart disease and some types of cancer. There are different vegetarian dietary patterns, some of which are nutritionally adequate for children, whereas other may lack some essential nutrients.

Ambroszkiewicz J et al (2004) examined 22 vegetarians and 13 omnivores in age 2-10 years. Average daily dietary energy intake and the percentage of energy from protein, fat and carbohydrates were similar for both groups of children. They observed that in vegetarian diet there is a high rate of fiber nearly twice as high as in omnivorous diet. The serum concentration of leptin was lower in vegetarians (3.0 ± 1.1 ng/ mL) than in nonvegetarians (5.1 ± 2.0 ng/mL) (p < 0.01).

Their results suggest that vegetarian diet may be accompanied by lower serum leptin concentration. [11]. Mi-Hyun Kim et al (2015) compare serum leptin levels between Korean postmenopausal longterm semi-vegetarians (n = 27), who maintained a semi-vegetarian diet for over 20 years and a group of non-vegetarian controls (n=27). The vegetarians showed significantly lower serum levels of leptin (p <0.05) than the non-vegetarians.[5].

Maelán Fontes–Villalba et al (2016). In a randomised, open-label, cross-over study, 13 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to eat a Palaeolithic diet based on lean meat, fish, fruits, vegetables, root vegetables, eggs and nuts, or a diabetes diet designed in accordance with current diabetes dietary guidelines during two consecutive 3-month periods.

The patients were recruited from primary health-care units and included 3 women and 10 men [age (mean ± SD) 64 ± 6 years; BMI 30 ± 7 kg/m2; diabetes duration 8 ± 5 years; glycated haemoglobin 6.6 ± 0.6 % (57.3 ± 6 mmol/mol)] with unaltered diabetes treatment and stable body weight for 3 months prior to the start of the study. Outcome variables included fasting plasma concentrations of leptin .

Dietary intake was evaluated by use of 4-day weighed food records. 7 participants started with the Palaeolithic diet and 6 with the diabetes diet.

The Palaeolithic diet resulted in a large effect size (Cohen’s d = −1.26) at lowering fasting plasma leptin levels compared to the diabetes diet [mean difference (95 % CI), −2.3 (−5.1 to 0.4) ng/ml, p = 0.023]. Conclusions: Over a 3-month study period, a Palaeolithic diet resulted in reduced fasting plasma leptin levels compared to the currently recommended diabetes diet [10].

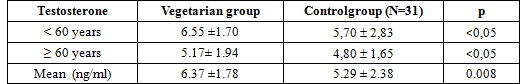

Table 12. Testosterone of study groups

In our study, the levels of testosterone was significantly higher in vegetarian men compared to non vegetarian men (6.37 ±1.78 vs 5.29 ± 2.38 ng/ml, p=0.008). The concentration of testosterone was significantly higher in vegetarian men < 60 yrs compared to non vegetarian men (6.55 ±1.70 vs 5,70 ± 2,83 ng/dl, p <0,05), and the levels of Testosterone was significantly higher in vegetarian men ≥ 60 yrs compared to non vegetarian men (5.17± 1.94 vs 4,80 ± 1,65 ng/dl, p <0,05).

In our study, the levels of testosterone was significantly higher in vegetarian men compared to non vegetarian men (6.37 ±1.78 vs 5.29 ± 2.38 ng/ml, p=0.008). The concentration of testosterone was significantly higher in vegetarian men < 60 yrs compared to non vegetarian men (6.55 ±1.70 vs 5,70 ± 2,83 ng/dl, p <0,05), and the levels of Testosterone was significantly higher in vegetarian men ≥ 60 yrs compared to non vegetarian men (5.17± 1.94 vs 4,80 ± 1,65 ng/dl, p <0,05).

William Rosner et al (1987) looked at the levels of testosterone and sex-hormone-binding-globulin (SHBG; testosterones transport-protein) on two different diets with the same net calories. One diet was high in meat, the other was high in whole-grains. He found that testosterone and SHBG levels were 23% and 33% respectively higher in the subjects eating whole-grains compared to the subjects eating meat [22]. A study done in England (1990) found that vegans had 7% higher testosterone and 23% higher SHBG than omnivores [23]. A study done ten years later, also in England, looked at hormone levels in vegan, vegetarian, and meat-eating men and found that testosterone and SHBG levels were about 15% higher in vegan men compared to meat-eaters. The vegan men had about 10% higher levels than vegetarians [24]. Recently Yauniuck Yao Dogbe et al (2015) examined the levels of endogenous sex hormones in vegetarian and non-vegetarian males in a case-control study of 52 healthy males (22 vegetarians and 30 nonvegetarians. They found that the mean serum testosterone levels of vegetarians (20.0 nmol/L) was significantly lower (p=0.022) than in non-vegetarians (24.6 nmol/L) [33].

So why do we hear all the time that vegans have low testosterone? Many lay people argue that since it is well known that a vegan diet will increase SHBG, that this will inevitably bind up all your free-testosterone and render it useless, they suggest eating meat to lower SHBG and thus “free-up” this bound-testosterone. What these lay people don’t understand is that SHBG is positively correlated with testosterone [25-26]. Levels of both testosterone and SHBG have drastically declined in industrial-societies since the 1920’s [27-28]. The cause of this is thought to be caused by the metabolic-syndrome, a disease like state that causes low SHBG and testosterone[29-30]. Fortunately people following plant-based diets don’t have metabolic-syndrome [31-32].

Conclusions

Amelioration of multiple cardiometabolic risk factors such as BMI, arterial blood pressure, lipid profile, hsCRP and testosterone concentration was associated with vegetarian diet long-term in male subjects. However, long-term vegetarian diet could cause hyperglycemia and hypoleptinemia. Those effects appeared to be correlated with the vegetarian duration (more than 21 years).

REFERENCES

- Christopher L Melby, M Lynn Toohey, and Joan Cebrick (1994). Blood pressure and blood lipids among vegetarian, semivegetarian, and nonvegetarian African Americans. Am J Clin Nut,’ 1994;59: 103-9. Printed in USA. © 1994 American Society for Clinical Nutrition.

- EA Spencer1*, PN Appleby1. GK Davey1 and TJ Key1 (2003). Diet and body mass index in 38000 EPIC-Oxford meateaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans. 1Cancer Research UK Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. International Journal of Obesity (2003) 27.728–734.

- PK Newby, Katherine L Tucker, and Alicja Wolk (2005). Risk of overweight and obesity among semivegetarian, lactovegetarian, and vegan women. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:1267–74.Printed in USA. © 2005 American Society for Clinical Nutrition.

- Sutapa Agrawal*, Christopher J Millett, Preet K Dhillon, SV Subramanian and Shah Ebrahim (2014). Type of vegetarian diet, obesity and diabetes in adult Indian population. Agrawal et al. Nutrition Journal 2014.13:89

- Mi-Hyun Kim1. Yun-Jung Bae2*. Comparative Study of Serum Leptin and Insulin. Resistance Levels Between Korean Postmenopausal Vegetarian and Non-vegetarian Women. Department of Food and Nutrition, Korea National University of Transportation, Jeungpyeong 368-701. Korea Division of Food Science and Culinary Arts, Shinhan University, Uijeongbu 480-701. Korea Clin Nutr Res 2015;4:175-181.pISSN 2287-3732 ∙ eISSN 2287-3740

- Ashwini (2016). A comparative study of metabolic profile, anthropometric parameters among vegetarians and non-vegetarians- do vegetarian diet have a cardio protective role. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016 Jun;4(6):2240-2245.pISSN 2320-6071 | eISSN 2320-6012

- Krithiga Shridhar1*, Preet Kaur Dhillon1. Liza Bowen2. Sanjay Kinra2. Ankalmadugu Venkatsubbareddy Bharathi3. Dorairaj Prabhakaran1. 4.Kolli Srinath Reddy5. Shah Ebrahim2. for the Indian Migration Study group. The Association between a Vegetarian Diet and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk Factors in India: The Indian Migration Study. October 2014 | Volume 9 | Issue 10 | e110586

- Yoko Yokoyama1. Neal D. Barnard2. 3.Susan M. Levin3. Mitsuhiro Watanabe 4.5Vegetarian diets and glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2014;4(5):373-382

- Shu-Yu Yang1. 2*†, Hui-Jie Zhang2†, Su-Yun Sun2. Li-Ying Wang2. Bing Yan2. Chang-Qin Liu2. Wei Zhang2 and Xue-Jun Li2 Yang et al. Relationship of carotid intima-media thickness and duration of vegetarian diet in Chinese male vegetarians. Nutrition & Metabolism 2011. 8:63.

- Maelán Fontes‑Villalba 1,6*, Staffan Lindeberg1, Yvonne Granfeldt2, Filip K. Knop3, Ashfaque A. Memon 1, Pedro Carrera‑Bastos1, Óscar Picazo4, Madhvi Chanrai5, Jan Sunquist1, Kristina Sundquist1 and ommy Jönsson. (2016) Palaeolithic diet decreases fasting plasma leptin concentrations more than a diabetes diet in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised cross‑over trial.

- Fontes‑Villalba et al. Cardiovasc Diabetol (2016) 15:80 [26]

- Ambroszkiewicz J1, Laskowska-Klita T1m, Klemarczyk W. (2004). Low serum leptin concentrationin vegetarian prepubertal children Roczniki Akademii Medycznej W Białymstoku. Vol. 49.2004. annale academiae medicae bialostocensis 103-105[25]

- Sumon Kumar Das1. Abu Syed Golam Faruque1*, Mohammod Jobayer Chisti1. Shahnawaz Ahmed1. Abdullah Al Mamun2. Ashish Kumar Chowdhury1. Tahmeed Ahmed1 and Mohammed Abdus Salam1. Nutrition and Lipid Profile in General Population and Vegetarian Individuals Living in Rural Bangladesh. Das et al., J Obes Wt Loss Ther 2012. 2:3

- Simone Grigoletto De Biase, Sabrina Francine Carrocha Fernandes, Reinaldo José Gianini, João Luiz Garcia Duarte (2007). Vegetarian Diet and Cholesterol and Triglycerides Levels. Catholic University at São Paulo, São Paulo, SP – Brazil- Arq Bras Cardiol 2007; 88(1) : 32-36

- Neal D. Barnard, MD, Joshua Cohen, MD David J. A. Jenkins, MD, Phd, Gabrielle Turner-mcgrievy, MS, Rd Lise Gloede, Rd, Cdebrent Jaster, MD Kim Seidl, MS, Rd Amber A. Green, Rd Stanley Talpers, MD. Low-Fat Vegan Diet Improves Glycemic Control and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in a Randomized Clinical Trial in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes care, Volume 29. Number 8. August 2006.

- Yee-Wen Huang1. Zhi-Hong Jian2. Hui-Chin Chang2. 3.Oswald Ndi Nfor2. Pei-Chieh Ko2. Chia-Chi Lung. Vegan diet and blood lipid profiles: a cross-sectional study of pre and postmenopausal women. Huang et al. BMC Women’s Health 2014. 14:55.

- Pranay Gandhi, Nilesh Agrawal, Sunita Sharma (2014). A Study of Vegetarian Diet and Cholesterol and Triglycerides Levels. Volume : 4 | Issue: 10 | October 2014 | ISSN – 2249-555X.

- Manish Verma1*, Poonam Verma2. Shabnam Parveen3.Karuna Dubey4 (2015). Comparative Study of Lipid Profile Levels in Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian PersonSchool of Biotechnology, IFTM University, Moradabad, U. P, India. International Journal of Life-Sciences Scientific Research (ijlssr), Volume 1. Issue 2. pp: 89-93 November-2015.

- Nico S. Rizzo, Phd, Joan Sabaté, MD, DrPh, Karen Jaceldo-Siegl, DrPh, Gary E. Fraser, MD, Phd. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns Are Associated With a Lower Risk of Metabolic Syndrome The Adventist Health Study 2. Diabetes care, Volume 34. May 2011.

- Penghui Shang PhD1. Zheng Shu MPH1. Yanfang Wang PhD1. Na Li PhD2. Songming Du PhD1. 3.Feng Sun PhD1. Yinyin Xia PhD4.Siyan Zhan PhD1 (2011). Veganism does not reduce the risk of the metabolic syndrome in a Taiwanese cohortAsia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20 (3):404-410.

- Chakole SA1. Muddeshwar MG2. Narkhede HP2. Ghosh KK3.Mahajan V3.Shende S3. Study of hsCRP and lipid profile in vegetarian and non –vegetarian Received 28 April 2014; accepted 22 May 2014.

- Andersson AM, Jensen TK, Juul A. Secular decline in male testosterone and sex hormone binding globulin serum levels in Danish population surveys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Dec; 92(12):4696-705.

- Anderson KE, Rosner W, Khan MS . Diet-hormone interactions: protein/carbohydrate ratio alters reciprocally the plasma levels of testosterone and cortisol and their respective binding globulins in man.Life Sci. 1987; May 4;40(18):1761-8.

- Key TJ, Roe L, Thorogood M. Testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, calculated free testosterone, and oestradiol in male vegans and omnivores. Br J Nutr. 1990 Jul; 64(1):111-9.

- Allen NE, Appleby PN, Davey GK. Hormones and diet: low insulin-like growth factor-I but normal bioavailable androgens in vegan men.

- Br J Cancer. 2000 Jul; 83(1):95-7 .

- De Ronde W, van der Schouw YT, Muller M.. Associations of sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) with non-SHBG-bound levels of testosterone and estradiol in independently living men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jan;90(1):157-62

- De Ronde W, van der Schouw YT, Pierik FH.. Serum levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) are not associated with lower levels of non-SHBG-bound testosterone in male newborns and healthy adult men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005 Apr; 62(4):498-503

- Andersson AM, Jensen TK, Juul A. Secular decline in male testosterone and sex hormone binding globulin serum levels in Danish population surveys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Dec; 92(12):4696-705.

- Travison TG, Araujo AB, O’Donnell AB. A population-level decline in serum testosterone levels in American men.J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Jan; 92(1):196-202. Epub 2006 Oct 24.

- Laaksonen DE, Niskanen L, Punnonen K. Testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin predict the metabolic syndrome and diabetes in middle-aged men. Diabetes Care. 2004 May; 27(5):1036-41

- Li C, Ford ES, Li B (2006). Association of testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in men. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jul;33(7):1618-24.

- Valachovicová M, Krajcovicová-Kudlácková M, Blazícek P (2006). No evidence of insulin resistance in normal weight vegetarians. A case control study. Eur J Nutr. 2006 Feb;45(1):52-4.

- Hung CJ, Huang PC, Li YH.. Taiwanese vegetarians have higher insulin sensitivity than omnivores. Br J Nutr. 2006 Jan;95(1):129-35.

- Yauniuck Yao Dogbe. Levels of endogenous sex hormones in mal. Vegetarians and non-vegetarians University of Ghana. July, 2015.

Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam

Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam