EVALUATION THE RELATION BETWEEN

AGE AT THE TIME OF DIABETES DIAGNOSIS AND

GLUTAMIC ACID DECARBOXYLASE (GAD) ANTIBODY

IN NON- OVERWEIGHT, OBESE DIABETIC INDIVIDUALS

Tran Thua Nguyen

Hue Central Hospital, Vietnam Association of Diabetes and Endocrinology

DOI: 10.47122/vjde.2020.40.7

ABSTRACT

Objective: Evaluation the relation between age at the time of diabetes diagnosis and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody in non- overweight, obese diabetic individuals. Method: A cross-sectional study on 284 non overweight- obesity diabetic patients at Hue Central hospital from August 2017 to August 2019. All patients were measured autoantibodies glutamic acid decarboxylase (anti-GAD). GAD antibody- positive was determined when autoantibodies to GAD concentration was higher than 5 IU/mL. Clinical data (age, sex, weight, hight) were obtained. Age at the time of diabetes diagnosis was interviewed. Data were analysed by SPSS version 16.0 and Medcalc software. Results: The risk of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody- positive in non- overweight, obese diabetic individuals increased 2.7 time when aged at the time of diabetes diagnosis 50 and older. The cut-off of age at the time of diabetes diagnosis for detecting risk of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody- positive in non- overweight, obese diabetic individuals was 57. Conclusion: This study showed non- overweight, obese diabetic individuals should be screened for glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody at aged 50 and older

Key words: autoantibodies glutamic acid decarboxylase (anti-GAD), diabetic individual, non- overweight, obese, age at the time of diabetes diagnosis.

Main correspondence: Tran Thua Nguyen

Submission date: 3th May 2020

Revised date: 14th May 2020

Acceptance date: 26th June 2020

Email: [email protected]

“This is the result of a provincial science and technology project invested by the state budget in Thua Thien Hue province”. We would like to thank you for this support!

1. BACKGROUND

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) released new figures that highlight the alarming growth in the prevalence of diabetes around the world, that if there is no effective measure to prevent disease progression, by 2040, the number of people with diabetes worldwide will reach 642 million [6].

The age at the time of diabetes diagnosis is also a predictor factor of the presence of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody. We found that the recommended age for cut-off point for detection / diagnosis of type 2 diabetes with positive autoantibodies depending on the proportion of type 1 diabetes in the general population. For white race, the rate of autoimmune diabetes with positive autoantibodies is higher than for other races, so the cut-off point for type 2 diabetes screening has lower autoantibodies. The rate of autoimmune diabetes with positive autoantibodies among Asians is assessed to be lower than the white race, so a cut off point the ageat the time of diabetes diagnosis is recommended higher[1].

Objective: Evaluation the relation between age at the time of diabetes diagnosis and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody in non- overweight, obese diabetic individuals.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects: Non overweight- obesity diabetic patientsover 35 years old, (BMI <23 at the time of the study) at the General Internal Medicine – Geriatrics Department and Endocrinology – Neurology – Respiratory department at Hue Central Hospital , from August 2017 to August 2019.

Selection criteria: Patients had qualify for:

– Diabetes was diagnosed according to the standards of Vietnam Association of Diabetes and Endocrinology (2016) [5].

– BMI < 23 ( non overweight- obesity).

-Age of disease detection ≥ 35 years old.

Exclusion criteria:

Patients disqualified prospective subjects from inclusion in the study with:

– Age of onset of disease <35 years old.

– BMI ≥ 23.

– History of gestational diabetes mellitus

2.2. Methods:

A described, cross-sectional study with convenience sampling.

– All patients were carried out taking parameters of age, sex, weight, height, age of disease detection.

– Quantified anti-GAD antibody by ELISA analyzer at Department of Biochemistry, Hue Central Hospital.

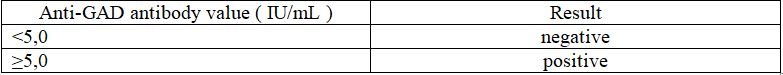

Table 2.1. Anti-GAD antibody reference value *:

* Each laboratory should establish its own reference values.

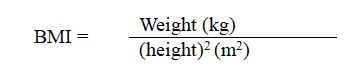

– Calculating BMI:

Table 2.2. Classification of BMI by WHO 2000 body index (BMI), apply to Asia [5]

Data were analysed by SPSS version 16.0 and Medcalc.

3. RESULTS

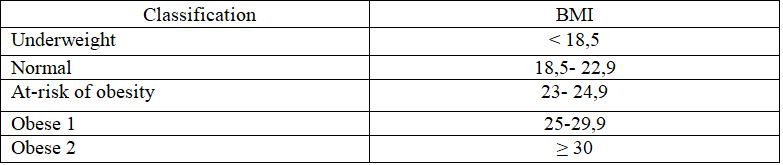

Table 3.1. Comparison of disease detection age between two groups of diabetic patients with positive and negative anti-GAD antibody.

Comments: The average age at the time of diabetes diagnosisin the group of positiveanti-GAD antibodiespatients was higher than the negative group: 59.84 ± 12.85 (age) compared to 52.45 ± 14.07 (years),the difference was statistically significant (p <0.05).

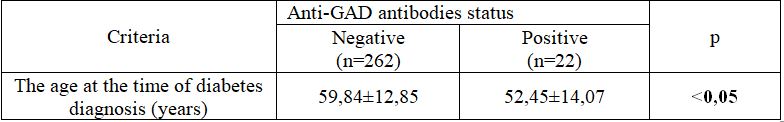

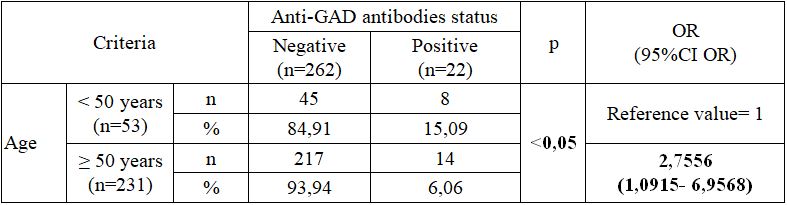

Table 3.2. The positive anti-GAD antibodies ratio for the age of detecting diabetes was under 50 years old

Comment: In the group of patients at the time of diabetes diagnosis under 50 years old, the rate of positive anti-GAD antibodies was 15.09%, the difference was statistically significant (p <0.05). In non overweight- obesity diabetic patientsat the time of diabetes diagnosis≥ 50 years old was increased relative riskof anti-GAD antibodies is 2.7 times higher.

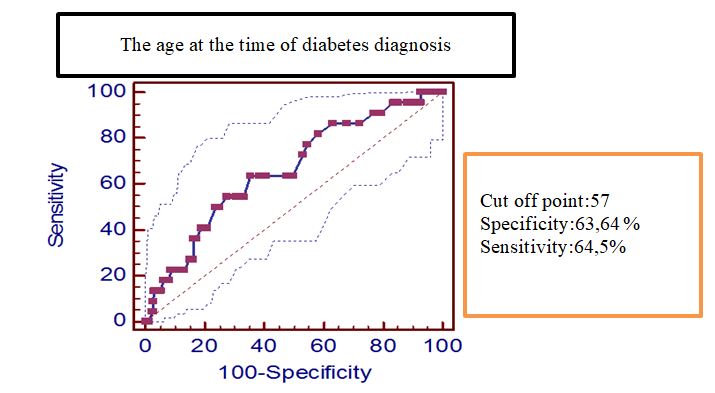

Figure 3.1. ROC curve of age at the time diabetes diagnosis predicts risk of positive anti-GADantibodies innon overweight- obesity diabetic patients.

Comments: When the age at the time diabetes diagnosiswas> 57, there was a risk of positive anti-GAD antibodies with an area under the curve (AUC) 0.66 (95% confidence interval: 0.602 – 0.715); sensitivity 64.5% and specificity 63.64%; p <0.01

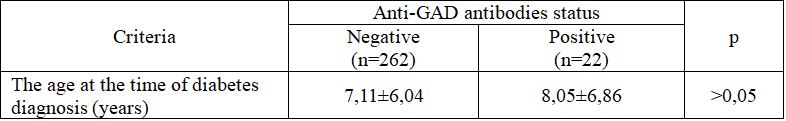

Table 3.3. Comparison of disease detection time between two groups of diabetic patients withpositive and negative anti-GAD antibodies.

Comment: The time to detect diabetes in the group with positive anti-GAD antibodies was greater than the negative group, the difference is not statistically significant (p> 0.05).

4. DISCUSSIONS

Age of detecting diabetes is also a predictor factor of the presence of anti-GAD antibodies. In our study (Table 3.1), the average age at the time of diabetes diagnosis in positive anti-GAD positive antibodies patient groups (52.45 ± 14.07) was lower than for patients withnegative anti-GAD antibodies (59, 84 ± 12.85), the difference was statistically significant (p <0.05). In Tran Quang Khanh’s study [10], the average age at the time of diabetes diagnosis withpositive anti-GAD antibodies (51.6 ± 12.6) was higher than that of patients with negative anti-GAD antibodies (51, 2 ± 11,4), the difference was not statistically significant (p> 0.05).

The age at the time of diabetes diagnosisin group of patients with positive anti-GAD antibodies earlier than negative group was 7.39 years. This result was larger than Nguyen Thi Thu Mai’s study [11]: patients with positive anti-GAD antibodies started the disease earlier than negative group with 4.04 years, but this difference was not statistically significant. Meanwhile, Tran QuangKhanh’s study noted that the difference in age of disease detection between two groups was insignificant and not statistically significant [10].

There was no consensus on the age at which autoantibodies should be screened in the population of diabetic patients. Zimmet suggested the age to detect type 2 diabetes with a positive autoantibody of 25 [17].

Many other authors had proposed the cut-off point for the detection of type 2 diabetes with positive autoantibodies was over 35 years old because it overlaps with the detection of classic type 1 diabetes in the age of 25-35 [8]. The Immunology of Diabetes Society had estimated that the minimum cut-off point for the age of detecting type 2 diabetes with positive autoantibodies varies between 25-40 years old and suggests 30 years old was the average age in detecting type 2 diabetes with positive autoantibodies [12].

In contrast, in the Asian race, Zhou noted that the age at the time of diabetes diagnosiswith positive autoantibodies in China is less than 40 years old in order to avoid overlap with the classic type 2 diabetes diagnosis [16]. Similarly, Tan and Thai noted that type 2 diabetic patients with positive autoantibodies in Singapore were often found in 40 years old [13]. Kobayashi presents the age at which detection of type 2 diabetes withpositive autoantibodies in the Japanese diabetic population is over 40 [9].

We found that the recommended age for cut-off point for detection / diagnosis of type 2 diabetes with positive autoantibodies depending on the proportion of type 1 diabetes in the general population. For white race, the rate of autoimmune diabetes with positive autoantibodies is higher than for other races, so the cut-off point for type 2 diabetes screening has lower autoantibodies. The rate of autoimmune diabetes with positive autoantibodies among Asians is assessed to be lower than the white race, so a cut off point the ageat the time of diabetes diagnosis is recommended higher.

According to the results of Table 3.2, among diabetes patients group was diagnosed under 50 years old, the rate of positive anti-GAD antibodies was 15.09%, the difference was statistically significant (p <0.05In non overweight- obesity diabetic patientsat the time of diabetes diagnosis≥ 50 years old was increased relative riskof anti-GAD antibodies is 2.7 times higher.So, these subjects do not rule out the possibility of becoming insulin dependent in the future.

According to Figure 3.1, using ROC curve of age at the time diabetes diagnosis predicts risk of positive anti-GADantibodies innon overweight- obesity diabetic patients was 57 with an area under the curve (AUC) 0.66 (95% confidence interval: 0.602 – 0.715); sensitivity 64.5% and specificity 63.64%; p <0.01

Our results were higher than other authors, and there was discussed about the association between positive autoantibodies in type 2 diabetics and the age at the time diabetes diagnosis:

– Fourlanos S. Author et al: a prospective study in Melboure, Australia, when comparing between two groups of type 2 diabetes patients hadpositive and negative anti-GAD antibodies, Fourlanos noted the age at the timetype 2 diabetes diagnosishad positive anti-GAD antibodies was less than 50 years old and this difference was significant compared to type 2 diabetes had negative anti-GAD antibodies. This was a predictive factor for the presence of anti-GAD antibodies [4].

– Author Tran QuangKhanh [10] used cut-off point to screen for autoantibodies being over 25 years old because the unknown rate of autoimmune diabetes with positive autoantibodies in the Vietnamese population. The author also did not record the difference in age, the age at the time diabetes diagnosis and diseaseaverage time between type 2 diabetes patients group with positive and negative autoantibodies.

In Finland, the type 2 diabetic population age at the time diabetes diagnosis under 45 years had a significantly higher rate of positive anti-GAD antibodies than the population group was diagnosed after 45 years old in Toumi’scross-sectional study [14].

– Carlson suggests that age over 60 is an important risk factor for both type 2 diabetes and type 2 diabetes with positive autoantibodies [2].

– Arikan believes that Turkey type 2 diabetes with positive anti-GAD antibodies were diagnosed at younger age than patients with negative anti-GAD antibodies significantly (45.1 years of age compared to 50, 8 years old) [1].

– UKPDS 25 study observed that there was a negative correlation between the rate of positive autoantibodies and the age of disease detection. The rate of positive anti-GAD antibodies decreases as patients were diagnosed diabetes at a higher age [15].

– UKPDS 70 study found that type 2 diabetespatients with positive autoantibodies were usually 4 years younger than negativeanti-GAD patients [3].

In contrast, Zinman commented that there was no difference in the rate of positive anti-GAD antibodies between ages based on data from the ADOPT study [18].

In Asia, Ishii’s research on the Japanese diabetes population had shown that type 2 diabetes patients with positive autoantibodies who had high anti-GAD antibodies titre were often older than type 2 diabetes patients with positive antibodies had a medium or low antibodiestitre [7].

Meanwhile, Hamaguchi did not record a difference in diagnostic age between type 2 diabetes patients with positive and negative autoantibodies. Wang noted that the rate of negative autoantibodies increases gradually as type 2 diabetes patients were diagnosed at an older age [5].

5. CONCLUSIONS

Conducting research on 284 non- overweight, obese diabetic individuals, we have some comments: The risk of positive anti-GAD antibodies in non-overweight, obese diabetic individuals increased 2.7 time when aged at the time of diabetes diagnosis 50 and older. The cut-off of age at the time of diabetes diagnosis for detecting risk of positive anti-GAD antibodies in non- overweight, obese diabetic individuals was 57.

REFERENCES

- Arikan E., Sabuncu T., et al. (2005), “The clinical characteristic of latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults and its relation with chronic complication in metabolically poor controlled Turkish patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus”, J Diabetes Complication, 19(5), pp. 254- 258.

- Carlson S., Midthjell K., et al. (2007), “Age, overweight and physical inactivity increase the risk of latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults: results from the Nord-Trndelag health study”, Diabetogia, 50, pp. 55- 58.

- Davis T.M.E., Zimmet P., et al. (2000), “Islet autoantibodies in clinically diagnosed type 2 diabetes: prevalence and relationship with metabolic control (UKPDS 70)”, Diabetologia, 48(4), pp.695- 702.

- Fourlanos S., C. Perry, M.S. Stein, J. Stankovich, L.C. Harrison, P.G. Colman (2006), “Clinical screening tool identifies autoimmune diabetes in adults”, Diabetes Care, 29, pp.970–975.

- Hamaguchi K., Kimura A., et al. (2004), “Clinical and genetic characteristics of GAD-antibody positive patients initially diagnosed as having type 2 diabetes”, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 66, pp. 163–171

- Hội Nội tiết & Đái tháo đường Việt Nam (2016), Khuyến cáo về bệnh nội tiết và chuyển hóa, Nhà xuất bản Y học, Hà Nội.

- Ishii M., Hasegawa G., et al. (2005), “Clinical and genetic characteristic of diabetic patients with high-titer (>10 000U/ml) of antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase”, Immunol Lett, 99(2), pp. 180- 185.

- Karvonen M., Kajander M.V., et al (2000), “Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide”, Diabetes Care, 23, pp. 1516- 1526.

- Kobayashi T., Tanaka S., et al. (2006), “Immunopathological and genetic features in slowly progressive insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults”, Ann N Y AcadSci, 1079, pp. 60- 66.

- Trần Quang Khánh (2010), Tỷ lệ kháng thể kháng Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase và kháng tiểu đảo tụy trên bệnh nhân đái tháo đường týp 2, Luận án Tiến sĩ Y học, trường Đại học Y Dược thành phố Hồ Chí Minh

- NguyễnThị Thu Mai (2010), Nghiên cứu một số đặc điểm lâm sàng, kháng thể kháng GAD và điều trị ở bệnh nhân đái tháo đường có BMI < 23, Luận văn Thạc sĩ Y học, trường Đại học Y Dược Huế.

- Pihoker C., Gilliam L.K., et al (2005), “Autoantibodies in diabetes”, Diabetes, 54, pp. 52- 60.

- Thai A.C., Ng W.Y., et al. (1997), “Anti-GAD antibodies in Chinese patients with youth and adult-onset IDDM and NIDDM”, Diabetologia, 40, pp. 1425- 1430.

- Toumi T., Carlson A., et al. (1999), “Clinical and genetic characteristic of type 2 diabetes with and without GAD antibodies”, Diabetes, 48(1), pp. 150- 157.

- Turner C., Stratton I., et al. (1997), “Autoantibodies to islet-cell cytoplasm and glutamic acid decarboxylase for prediction of insulin requirement in type 2 diabetes. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group (UKPDS 25)”, Lancet, 350(9087), pp. 1288- 1293.

- Zhou Z., Ouyang L., et al., (1999), “Diagnostic role of antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase in latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults”, Chin Med J (Engl), 112, pp. 554- 557.

- Zimmet P.Z, Tuomi T. et al (1994), “Latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults (LADA): the role of antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase in diagnosis and prediction of insulin dependency”, Diabet Med, 11(3), pp. 299- 303.

- Zinman B., Kahn S.E., et al. (2004), “Phenotypic characteristic of GAD antibody-positive recently diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes in North America and Europe”, Diabetes, 53(12), pp. 3193- 3120.

Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam

Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam Hội Nội Tiết – Đái Tháo Đường Miền Trung Việt Nam